P1: Introduction, the beginnings of consumer technology, and material sourcing

Introduction

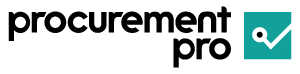

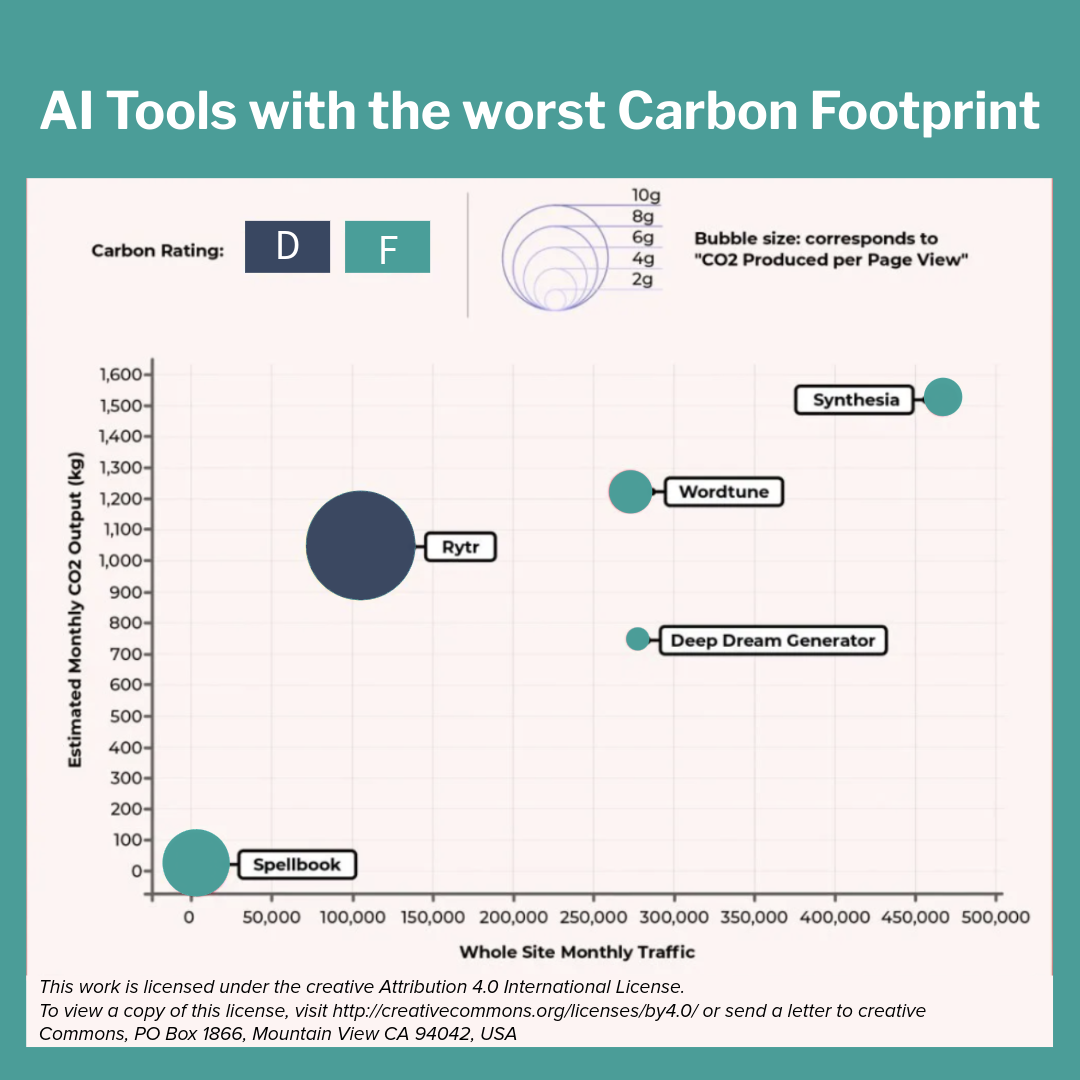

Globally, sustainability is a hot topic – with rising temperatures changing weather patterns and disrupting the balance of nature. It is a particular concern in the consumer electronics industry, where it is estimated that digital technology alone contributes to anywhere between 1.4-5.9% of greenhouse gas emissions, with around 31% of which being contributed by devices like smartphones, desktops, displays, and notebooks[1]. Throw AI into the mix, where the monthly carbon footprint of ChatGPT alone is the equivalent of 260 transatlantic flights, and environmental sustainability feels like a distant notion.

The United Nations Environment Programme notes that it takes 800kg of raw materials to produce a 2kg AI data centre computer, not to mention that they are a massive drain on water supplies. Plus, this all consumes a tremendous amount of energy.

In this first part of a three part series, I will dive into some of the most pivotal moments in consumer electronics before exploring raw material sourcing. In parts two and three, I will then look further along the supply chain at energy usage and supply chain logistics, right through to end-of-life and e-waste.

Our electronic lifestyles

In today’s connected world, electronics underpin nearly every aspect of daily life. From lighting and laptops to vehicles and communication tools, electronic systems have transformed the way we work, interact, and travel. And behind each device is a complex web of resources required to make it function. These materials are central not only to innovation but also to the long-term sustainability of the sector.

But how do you define this long-term sustainability?

The United Nations defined sustainable development as “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” Meaning that the challenge is for technology companies to continue pushing forward without exhausting the finite natural resources on which they depend – whether that be minerals from the Earth, ecosystems in the sea, or the stability of the atmosphere.

However, the production of consumer electronics relies heavily on those finite resources, including precious metals and rare earth elements (more about these resources here). Annually, approximately $60 billion worth of raw materials are lost as these valuable components end up in landfills or are incinerated. This not only depletes natural resources but also poses environmental hazards.

As we will see, the consumer technology industry has new devices regularly entering the market, and it is a big contributor to e-waste. Yet, according to one report by Grand View Research the global consumer electronics market is expected to grow at a CAGR of 6.6% between 2025 and 2030.

But first, let’s take a look at the evolution of consumer technology through a few key milestones.

The growth of consumer technology

The mainstream consumer technology market began to gather momentum in the late 1970s and early 1980s, with the release of products like Sony’s Walkman in 1979. Around the same time, IBM’s launch of the Personal Computer in 1981 changed the computing landscape as we know it – this was closely followed by home computers like the Commodore 64, Apple Macintosh, and Windows-based PCs which gained popularity, leading a movement towards more accessible computing for homes and small businesses. The video game industry also began to take hold during this time, with home consoles like the Atari 2600 introducing interactive entertainment to a mass audience.

In the 1990s, the rise of the Internet – particularly in the second half of the decade – began to transform how people accessed information and communicated. During this time, mobile phones also started to gain traction in the consumer space.

However, it wasn’t until the early 2000s that digital lifestyles started to become firmly established with the launch of Apple’s iPod in 2001, followed by the iTunes ecosystem. Flat-screen TVs, digital cameras, and DVD players also became common in households, while broadband Internet replaced dial-up giving users a much improved online experiences – with no more dial tone!

But consumer technology isn’t one to stand still, and by the late 2000s and into the 2010s, the technology experienced another, and quite significant, leap, this time with the growing capabilities of smartphones. It is devices like the iPhone in 2007 and the growing popularity of Android phones that led to the development of app ecosystems always-connected devices, and a growing dependence on mobile technology. Tablets, streaming services, and smart home devices all expanded the consumer tech landscape, setting the stage for the interconnected digital environments that continue to evolve today.

As we can see, consumer technology has grown over the last 50 years, but it was only in the last 25 years that the output began to skyrocket as the technology caught up with the vision.

So, now that we know a bit about the history of electronics and how fast this industry has already grown, let’s take a look at sustainability in consumer electronics and why it matters now more than ever.

What is sustainability in consumer electronics?

In a nutshell, consumer electronics sustainability is the practice of designing, producing, and using electronics in a way that reduces environmental impact, or put another way, “sustainable procurement” of electronics means making purchasing and supply-chain decisions that minimise harm to the environment and society.

In practice, this spans the entire product lifecycle: from responsibly sourcing raw materials, to energy-efficient manufacturing and transport, to reducing waste and ensuring end-of-life (EoL) recycling. In the UK and Europe, this approach is being increasingly supported by regulations and standards. For example, the EU Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE) Directive mandates separate collection and recycling of electronics. Industry bodies have also issued frameworks: the OECD’s ‘Due Diligence Guidance for Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas’ provides a five-step process for responsible sourcing. Likewise, the Responsible Minerals Initiative (RMI) and Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance (IRMA) set expectations and auditing tools for mining practices.

On the recycling side, standards like R2 (Responsible Recycling) certify e-waste recyclers to handle electronics safely and recover materials

When looking at consumer devices, my initial research highlighted, pretty fast, that a huge part of consumer waste is the phone market – which currently has an estimated market volume of $504.1 billion (in 2025). In the UK, over 90% of mobile phone users now own a smartphone, and globally, around 1.5 billion smartphones are sold each year.

Smartphones have complex, resource-intensive lifecycles, from extracting metals and minerals, and manufacturing in energy-intensive factories through to worldwide distribution and creating e-waste. The environmental and social impacts of creating these devices are big.

Because of the sheer scale of sustainability concerns that are entangled with smartphones in consumer electronics, I will focus a lot of attention here.

But, if sustainability is the goal, then repairability and recyclability must be the mechanisms that will help achieve that goal.

Smartphones and e-waste

Electronic waste generation, globally, is rising five times faster than documented e-waste recycling, according to the 2024 Global E-Waste Monitor report. In 2022, smartphones and similar devices generated about 62 million tonnes of electronic waste , a record high, and this figure is expected to increase to 33% by 2030. However, only around 22.3% of this e-waste is formally collected and recycled – with the rest often ending up in landfills or informal recycling, especially in developing countries. The report also foresees a drop in documented collection and recycling to 20% by 2030, owing to the “widening difference in recycling efforts relative to the staggering growth of e-waste generation worldwide.”

In the UK alone, e-waste totalled roughly 1.7 million tonnes in 2020 (the third-largest in Europe). According to the WWF, this includes the equivalent of over 11 million phones discarded that year. However, this may be an understatement according to another report ‘E-Waste Guide – Facts & Statistics’ which indicates that the figure could be twice as much. Meanwhile, many used devices are simply stored in drawers: an estimated 12 million unused phones sit idle in UK homes. The value locked in these unused devices has been estimated at £850 million (if refurbished and resold).

Despite the piling waste, mobile phones alone are forecast to grow 2.3% year-over-year in 2025 to 1.26 billion units and whilst these devices have their benefits, and mobile operators and technology providers are collaborating to develop more sustainable communication systems, for instance, Apple has increased its use of recycled content in products and both Back Market and Fairphone advocate for repairability and recyclability, the market currently continues to favour frequent device updates and feature-rich releases over repairability.

A driving force in mass consumerism is product marketing strategies that encourage frequent updates, not only digital updates, but physical product updates. Take the iPhone by Apple as an example. It releases a new model every year – and since the iPhone 6, it has started to offer different levels of the same product – each giving slightly tailored experiences. And whilst the mass marketing of these “must have” products exacerbates the problem, the reality is, the sustainability impact starts long before consumers buy the product. In fact, it starts from the very first rung of the whole product supply chain ladder – and it doesn’t end, even when the life of the product does.

But where does all that source material come from? And what is its impact? Let’s look at where it all begins. Material sourcing.

Material sourcing

Consumer electronics depend on a wide range of materials, from common metals to rare earth elements (REEs), to meet growing global demand. However, the ways these materials are sourced – and the environmental and ethical consequences – vary widely. Understanding the distinction between raw materials and REEs is important when it comes to understanding the supply chain and sustainability challenges the industry faces.

The difference between raw materials and rare earth elements

Raw materials and REEs play different roles in consumer electronics and each follow distinct supply chains. Raw materials tend to include metals, plastics, and ceramics used in structural and electrical functions. In contrast, REEs are used in small quantities for highly specialised purposes, such as magnets and display technologies. Both categories face sustainability hurdles, but for different reasons – ranging from mining ethics to processing complexity.

Raw materials

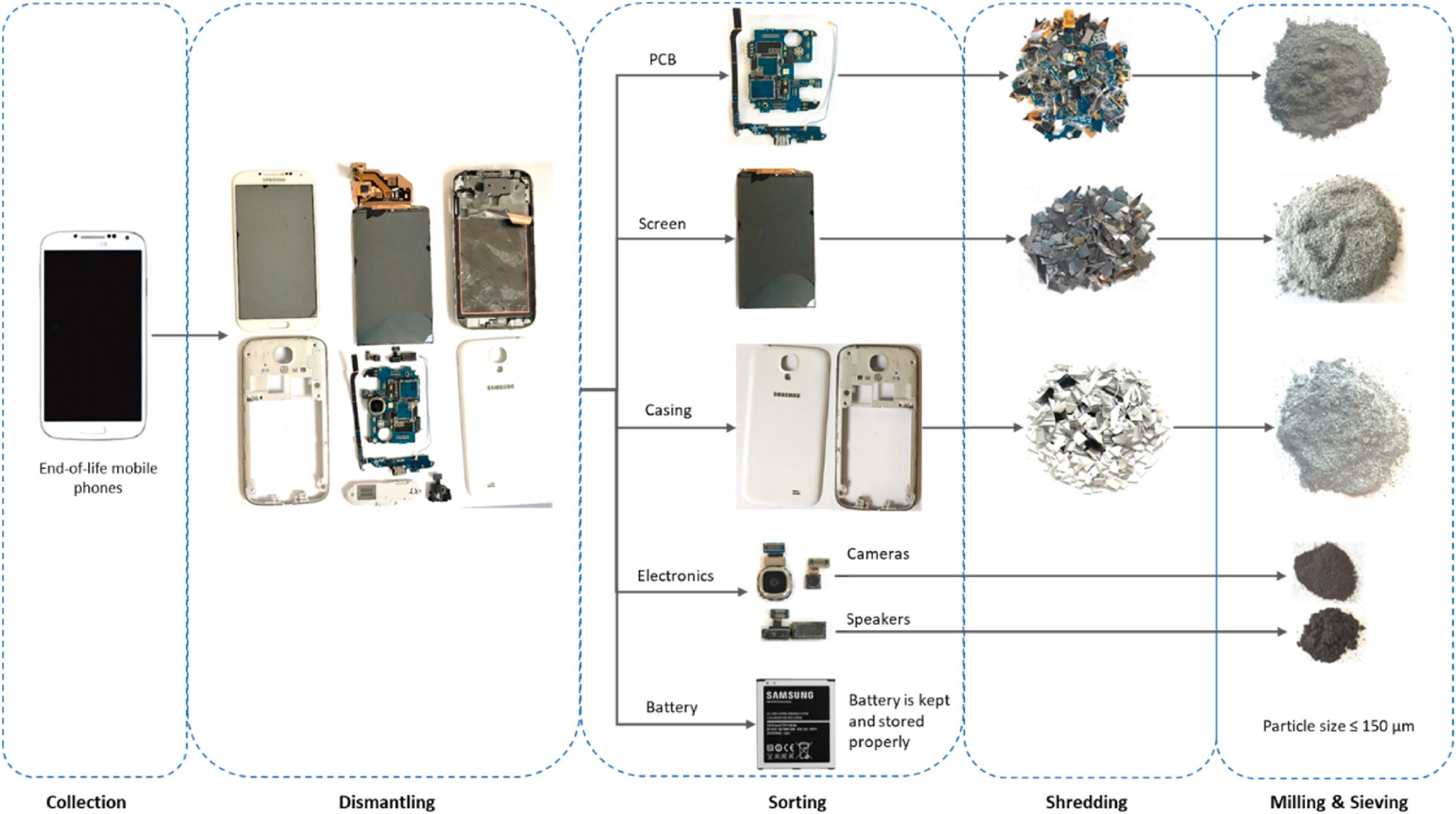

A modern mobile phone is composed of approximately 40% plastics, 35% metals, and 25% ceramics and glass by mass [2]. Key components include printed circuit boards (PCBs), screens, casings, speakers, cameras, and batteries – each containing varying concentrations of base, precious, and critical metals.

Printed circuit boards are particularly metal-rich, with copper alone accounting for around 27.8% of PCB mass, making up nearly 65% of its total metal content. Other important metals include aluminium, nickel, tin, and iron, along with smaller quantities of gold, silver, palladium, and platinum. REEs such as neodymium and erbium are also present, primarily in microphones and vibration components. In total, over 60 elements – including those on the EU critical materials list – may be used in phone production [2].

Per tonne of discarded phones, known as end-of-life mobile phones (EoL-MPs), the material value can be considerable. One tonne may contain up to 53kg of copper, 141g of gold, 270g of silver, 10g of platinum, 18g of palladium, and 3.3kg of rare earth elements. These concentrations are often far higher than those found in natural ores [2].

Despite the high resource value, mining and sourcing many of these materials come with serious social and environmental consequences. Tin, tungsten, tantalum, and gold (collectively known as 3TG) are classified as conflict minerals when sourced from regions such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, where extraction has been linked to armed conflict and human rights violations. Cobalt, often used in batteries, is similarly associated with exploitative labour practices and unsafe working conditions.

To address these issues, regulatory frameworks have been introduced:

- OECD Due Diligence Guidance outlines steps for responsible sourcing from high-risk areas

- EU Conflict Minerals Regulation mandates importers to verify that their 3TG sourcing is conflict-free

- Responsible Minerals Initiative (RMI) provides audit and reporting tools, including the Cobalt Reporting Template (CMRT) and Responsible Minerals Assurance Process (RMAP)

- Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance (IRMA) certifies mines against social and environmental standards

Fairphone, a Dutch smartphone maker, exemplifies ethical sourcing by tracing 23 target materials and prioritising recycled or Fairtrade-certified inputs. For example, tin and tantalum in Fairphone 4 are sourced from RMI-audited smelters or artisanal small-scale mining projects. Most mainstream manufacturers now publish supplier audits, but often rely on multi-tiered global networks that can obscure traceability.

Recycling is one way to reduce dependency on primary extraction. However, only a small fraction of materials in consumer devices currently comes from recycled sources. For example, Apple reported that 24% of the materials it shipped in 2024 were either recycled or renewable. Still, the vast number of devices in circulation – estimated at 18 billion in 2025 – represents a substantial opportunity for urban mining. The five billion phones discarded by 2022 alone were estimated to contain recoverable metals worth around $9.25 billion [2].

Rare Earth Elements

REEs, while also mined, are not classified with 3TG minerals and are used in much smaller volumes. However, they are equally essential to the functionality of tech like smartphones. Elements like neodymium and dysprosium are used in the production of strong permanent magnets that can be found in items such as haptic motors and speakers. Elements such as europium and terbium contribute to the vibrant colours in display screens. Unlike 3TG, the challenge with RREs is not their scarcity in the Earth’s crust (apparently, they actually aren’t rare), but it is the environmental complexity of separating them from ore – because they tend to occur together, they require intensive mining processing. This is a concern for the environmental footprint of REE mining, particularly in China, which is a dominant player in the global supply chain.

However, the recycling of REEs is beginning to take shape. UK startup HyProMag is developing methods to recycle rare earth magnets from scrap electronics. Meanwhile, researchers at Queen’s University Belfast are working on ionic liquid-based separation techniques for recovering REEs from waste devices.

An important distinction

Both raw materials and REEs are finite in practice, but for different reasons. Raw materials can become restricted because of geopolitical instability, lack of regulatory oversight, or exploitative labour practices. The limitations of REEs are based on the environmental cost of extraction and the economic viability of refining processes.

In both cases, the finite nature of these resources is pushing companies and researchers to explore more sustainable procurement strategies, including recycling initiatives and the search for alternative materials.

To understand the distinctions between raw materials and REEs is to enable the understanding of different sustainability challenges that are facing the electronics industry from the very first physical element. Which is why planning and logistics from the offset are important. It also highlights why both ethical sourcing and investment in circular approaches are becoming ever more important.

So, as we’ve seen, the consumer electronics industry is a fast-growing market.

It has witnessed staggering growth over the years, and by 2034 it is expected to exceed $1.4 trillion. Such fast and voracious expansion, however, brings with it a number of challenges.

Now we know a bit more about consumer products, how they are sourced, and the materials they use, the next question is, how do these materials get from point A to point B and how much energy does it take?

In part 2, I take a look at energy consumption and the supply chain.

Bib list:

[1] Narendra Singh and Oladele A. Ogunseitan (2022) ‘Disentangling the worldwide web of e-waste and climate change co-benefits’, Science Direct. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2773167722000115

[2] Gómez et al. (2023) ‘Critical and strategic metals in mobile phones: A detailed characterisation of multigenerational waste mobile phones and the economic drivers for recovery of metal value’, Science Direct. Available at:

1-s2.0-S0959652623022576-main.pdf