P2: Energy usage and supply chain logistics

There have been three industrial revolutions, and we are in the midst of the fourth. And, though the first two combined were arguably bad for the planet, what is clear is that the “take-make-dispose” model of electronic consumerism today is a big concern. Because every action has a consequence.

Consumer electronic devices today are both physical and digital. Making and using these devices takes vast amounts of energy. And because consumers have been conditioned to get everything immediately, thanks to 24/7 online shopping and clever algorithms tracking habits, it means that the rapid expansion of digital lifestyles has contributed to increased energy demands, increased manufacturing, and increased waste.

Part one, a recap

In part one of this three-part series, we witnessed how the prolific growth of consumer electronics is contributing to the rise in global temperatures and depleting finite resources.

Smartphones, laptops, and other consumer technologies rely on these finite resources, which include precious metals and rare earth elements, each of which carries environmental and ethical challenges from extraction through to disposal. Despite this, the market continues to grow, driving more frequent upgrades and causing an ever greater rise in e-waste.

Electronics account for an estimated 1.4-5.9% of global greenhouse gas emissions, with smartphones, computers, and displays responsible for nearly a third of that total. The energy and materials required for data centres and devices, including the massive quantities of raw materials and water, underline the sector’s weighted ecological footprint. Yet, the consumer electronics market continues to expand and is projected to grow at a 6.6% CAGR between 2025 and 2030.

In part two, I will look at energy and supply chain logistics, exploring the energy usage of some key consumer electronic devices, the impact of manufacturing, and how companies can reduce their environmental footprint long before a product reaches the consumer. I will also look at some companies that are already making steps to enable businesses of all sizes to achieve a lower carbon footprint.

For this article, I’d like to thank:

Jude Pullen, Creative Technologist, for his generosity of time and for sharing his insights on design and repairability.

Ronald Wilting, CEO of Forefront RF, for explaining how the company’s Foretune technology is helping to reduce energy use and wastage.

Elmar Kert, Co-Founder and CEO at Sluicebox, for his insights into carbon tracking and how digital tools can make supply chains more transparent, measurable, and sustainable.

Why consider energy usage when thinking about supply chain logistics?

Electronic devices are part of day-to-day life. In fact, in the modern world, you’d be hard pushed to find many people who can live without the aid of electronics in some form. And so, the consumer electronics industry is quite a lucrative one. The worldwide revenue generated in 2025 is estimated to be anywhere between $950 billion-$1.2 trillion, depending on the data source and the market definition. Statista takes a balanced approach and estimates that it currently stands at $1 trillion.

It’s not only revenue sources that vary, market growth forecasts also estimate growth to be between 6.6% CAGR between 2025-2023 (Grand View Research) or 2.8% (Statista). Whilst this shows that there is some uncertainty in long-term projections, the overall trend is clearly that the market will continue to expand.

However, all these electronic consumer devices in this expanding market use energy, and this energy use has a direct and measurable impact throughout a product’s lifecycle.

If we look at smartphones, laptops, and desktop PCs, what do they all have in common? They connect us to the Internet. This might appear harmless – a search here and there. A little video running in the background. Composing a fun image created by Generative AI. Finding a really delicious recipe, perhaps using AI to use up all of the ‘bits’ that are hanging around in the fridge. But if we look at Internet access in 2024, it had reached an estimated 68% of the global population with roughly 80-90% of people accessing social media via a smartphone.

These digital habits alone could collectively use up around 40% of a person’s individual carbon footprint allowance – which would be in line with keeping global warming below 1.5°C – and around 55% of the sustainable limit for mineral and metal use[2]. And that’s just on Internet access.

Let’s look at this energy consumption a little further:

Energy consumed by a device in everyday operation

Typical smartphone measurements place the annual electricity use at about one to five kWh per phone per year, depending on usage and charging[3]. Typical household/business Laptops, use roughly 20 to 75kWh per year, depending on model and usage. More intensive use pushes that number higher. Whereas desktops and monitors can use up to hundreds of kWh per year.

Individually, it might not seem like much – the equivalent of a short drive somewhere, maybe. But this is only three devices of the many that are out there. And together, globally, the usage and impact build up. Of course, the carbon intensity of the electricity used to run devices will depend on factors such as the country or region; for example, a coal-heavy grid is more carbon-intensive, whereas renewables-rich grids are less so, but add it all together, and it creates a highly carbonised environment.

Production, materials, component fabrication

Life Cycle Assessments (LCAs) consistently show that manufacturing more often than not accounts for the lion’s share of lifecycle impact for small electronics. For smartphones and laptops, studies report that manufacturing can account for c.70-80% (or more) of lifecycle greenhouse-gas impact[1].

This is because manufacturing consumes large amounts of electricity and process energy in chip fabs, display fabs, and materials refining; fabs are electricity-intensive, plus there is process heat and upstream energy in metal and chemical production. The embodied energy is a combination of grid electricity, industrial process energy, and energy used upstream in raw-material mining and refining[4]. This energy use creates a large “invisible” environmental burden that is built into the product before it is even used.

As Elmar Kert, Co-Founder and CEO at Sluicebox explained, the manufacturing phase – especially semiconductor and component fabrication – presents the biggest opportunities to reduce energy and emissions.

“These processes are extremely energy-intensive and rely heavily on high-GWP gases and complex materials. Improving process efficiency, shifting to renewable energy in fabs, and using smarter component selection at the design stage can deliver the largest reductions,” he said.

Kert added that integrated circuits (ICs), semiconductors, and microprocessors consistently rank among the top contributors due to their energy-intensive production and long supply chains. “But depending on the product, mechanical and electromechanical parts such as housings or motors can also be major drivers. This is why having component-level visibility is so critical – you often find surprises in unexpected places.”

Supply chain logistics and associated energy

Transport, warehousing, and distribution add additional energy burdens. The distance, the chosen method of transport, and frequency of shipments will determine the exact amount of energy used and its carbon footprint – this can often be difficult and/or time-consuming to track.

To address this, Sluicebox’s Component Carbon Intelligence framework enables companies to map and quantify the carbon footprint of each component across the entire supply chain. Built on its Generative LCA engine, the platform replaces manual spreadsheets with automated, audit-ready data that scales across portfolios.

“Our technology connects the missing dots between design, sourcing, and carbon data,” said Kert. “By linking each manufacturing part number to verified supplier and transformation data, we help teams identify and act on their biggest emissions hotspots.”

Sluicebox also provides “what-if” scenario modelling that allows manufacturers to simulate the impact of supplier, material, or location changes before implementing them. Companies can see in real time how different sourcing decisions will affect their footprint, explained Kert. “This gives them confidence in reduction paths before investing real-world effort or cost.”

Infrastructure energy related to device use

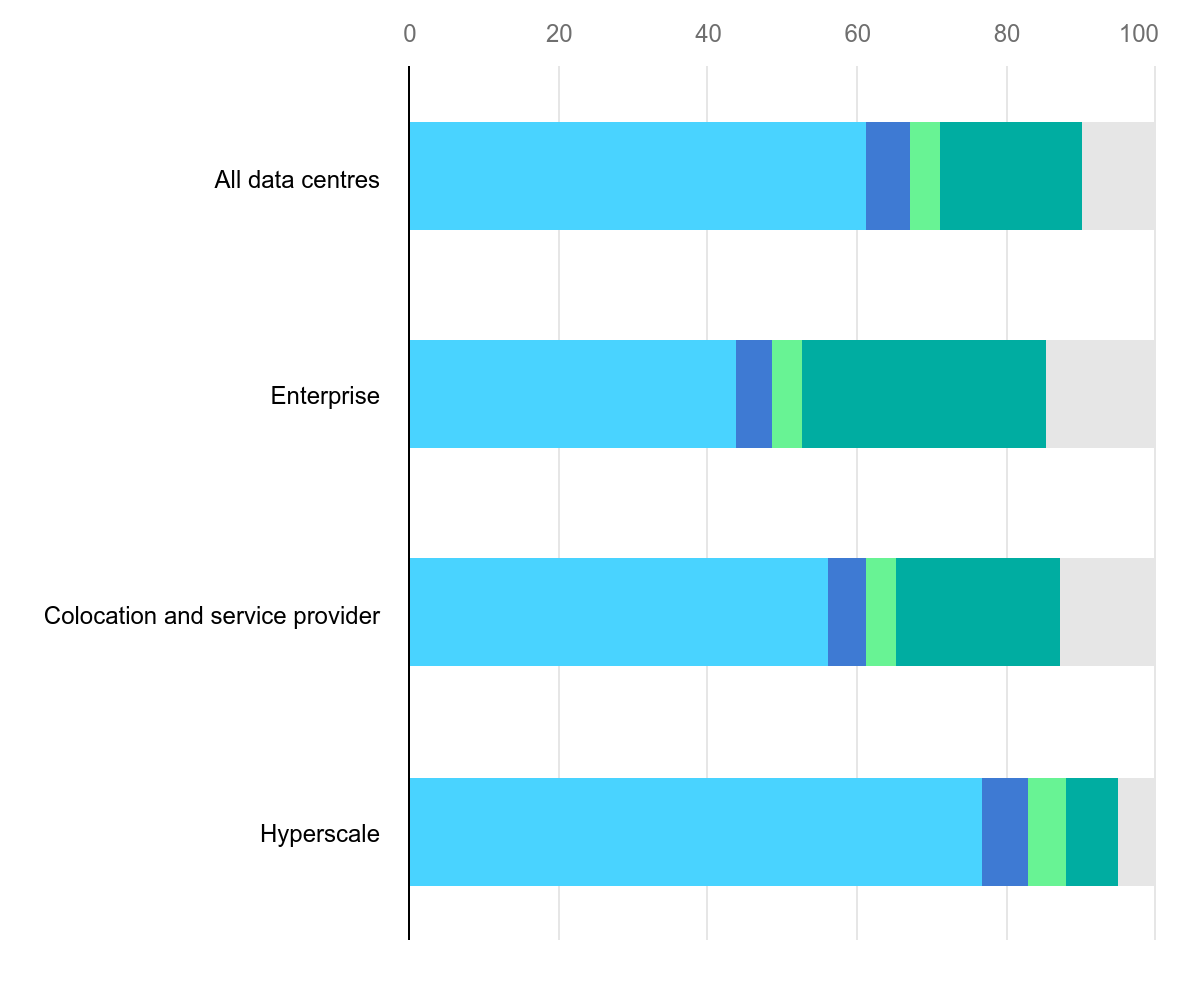

The ICT ecosystem – including networks, data centres, and devices – is an ever-growing electricity load. According to the International Energy Agency’s 2024 assessment, global data centre electricity usage reached around 416TWh in 2024 – 1.5% of the world’s electricity consumption, and that figure is projected to more than double by 2030 to 945TWh, primarily driven by AI and Cloud workloads.

Cornish-based digital design and development studio, Papaya-Studio, noted that if it were a country, the Internet would be the 14th largest polluter, on par with the 3.8% of global carbon emissions created by the aviation industry.

Reducing energy consumption and emissions

As we have seen, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions occur throughout a product’s lifecycle, but the majority of these emissions stem from production rather than use. Manufacturing, which includes mining, refining, chip fabrication, assembly, and transport to market, collectively accounts for up to around 80% of a device’s total footprint[1].

Kert believes that the industry is now moving towards real-time, transaction-level carbon tracking: “The emergence of digital product passports and AI-enabled supplier engagement will accelerate this. Within a few years, companies will be able to access live carbon intelligence alongside price and availability, which will turn sustainability into an operational metric, not a report,” he said.

He added that the most meaningful changes of the next few years will come from process decarbonisation in fabs and assembly lines, smarter design decisions that integrate carbon data early in R&D, and shared data standards that make carbon a common field in procurement systems. Once that happens, “the ripple effect across suppliers will be massive.”

As we can see, tracking carbon is an important step in enabling suppliers and distributors to reduce their carbon footprint. So understanding the impact of decisions on sourcing, component design, and logistics early on can determine much of a product’s carbon footprint long before it reaches the consumer.

Once a company understands where its carbon footprint is coming from, it can start to prepare for change.

Now we understand that one of the most energy-intensive stages of product development is semiconductor fabrication and assembly; one of the ways to reduce the ecological burden of consumer electronics production in this space is to reduce the amount of materials required by developing adaptable, multifunctional technologies that consolidate several parts into one efficient design.

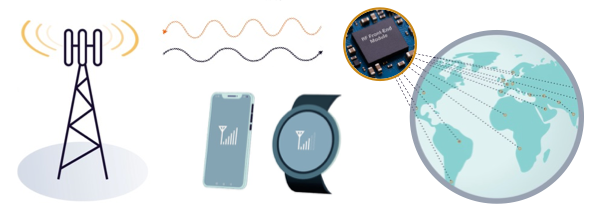

So, let’s take a look at a tangible case study of a company applying this principle to re-engineer how radio frequency components are designed and produced.

Forefront RF: a case study

Forefront RF is a UK-based semiconductor company that develops Foretune, a tuneable RF front-end technology that replaces dozens of fixed filters and switches with a single adaptive module. I spoke to Ronald Wilting to understand more about the technology and how it is helping to reduce energy usage and supply chain burden.

Whiting explained that in conventional smartphones and wearables, each frequency band requires a dedicated SAW (surface acoustic wave) or BAW (bulk acoustic wave) filter – made from lithium tantalate, ceramics, and metal plating – all of which consume energy and critical raw materials during manufacture. Foretune eliminates this duplication by creating a single duplexer that adjusts to different frequencies, enabling one global hardware platform instead of many regional variants.

This design delivers measurable sustainability benefits, as Whiting explained: “Forefront RF’s internal analysis shows that replacing a traditional SAW-based low-band front-end with a single Foretune module can cut material usage in the RF subsystem by over 50%, PCB footprint by up to 70%, component count by more than 80%, leading to reduced assembly energy and testing time.”

Fewer components mean fewer fabrication and assembly steps, translating to lower factory energy consumption and reduced test and packaging waste.

From a logistics perspective, a single global module also simplifies production, shipping, and warehousing. By removing the need to produce multiple regional SKUs, Whiting says that manufacturers can consolidate production lines, reduce transport energy by up to 30%, and lower packaging-related emissions.

Crucially, Foretune is manufactured using standard CMOS processes, avoiding materials such as lithium, tantalum, and gold plating. This not only reduces dependency on some of those critical raw materials I mentioned in part one, but also simplifies recycling at the product’s end of life, since silicon and copper are easily recovered through existing electronics recycling streams.

Designing for longevity and repairability

Improving energy efficiency cannot rely solely on cleaner energy sources. It also depends on how products are designed, upgraded, and repaired. Creative Technologist Jude Pullen argues that repairability, upgradability, and standardisation are key to cutting unnecessary production and extending product lifespans.

Pullen believes that designing hardware with the future in mind will limit waste and the energy required to build entirely new devices. Taking printed circuit boards (PCBs) as an example, he points out that many of them are custom-built, which means they are often treated as single-use designs with no practical alternative or modularity. This is an area he believes that design thinking could really come into play. Rather than accepting custom PCBs as inherently unrepairable, engineers could consider how these boards are laid out, accessed, and maintained. Repairability, he argues, should form the foundation of electronic design, particularly for components that are bespoke or tightly integrated.

A 2020 report from Green Alliance, ‘A circular economy for smart devices’ shows that extending a phone’s lifespan from two years to four can halve its annual carbon footprint. This, in turn, reduces the carbon footprint at the manufacturing stage, which we know contributes to around 80% of a smartphone’s carbon impact[1].

Designing for repairability and standardisation can also yield major efficiency gains. Pullen explained that if we, as an example, take the many different types of batteries that are available, it is an unnecessary environmental burden.

“We should absolutely be using a standardised battery, not buying something which is two millimetres longer, and hence is what I would call ‘exotic’ … It renders it unrepairable by being exotic and for really no ostensible benefit. I think that’s the responsibility a designer should have,” he said.

He added that when components such as batteries follow shared standards, it makes life easier for consumers to repair something because they’ll know what to buy. It extends a product’s lifecycle and reduces emissions and waste by lowering energy and resource consumption across the lifecycle.

Where Pullen focuses on design principles that prevent waste before it happens, Kert approaches the same challenge from the data side – enabling manufacturers to measure, understand, and reduce emissions across their entire supply chain. Together, their perspectives show how sustainability can be built into both the physical design of products and the digital systems that manage their creation.

Supply chain efficiency and stability

Supply chain sustainability goes hand in hand with energy reduction. Every shipment, warehouse, and redesign consumes energy and adds to the overall footprint. Yet supply chains in the electronics industry are often built around thousands of slightly different components, as Pullen has already illustrated: batteries are one example of many that cause unnecessary fragmentation across the supply chain.

“There is one website that has over 5,000 SKUs. That’s just one company for lithium batteries … Some of them are just five milliamp hours difference and one millimetre difference extra. Why isn’t that just consolidated as one battery? It’s ridiculous. Such small variations are considered ’rounding errors’ in a Tolerance Stack, so they seem an unnecessary SKU proliferation.”

As Pullen argues, the problem here isn’t that a one-millimetre variation is problematic on its own; rather, the issue is the unnecessary spread of near-identical sizes – for example, 30, 31, 32, and 33mm – when each already has a tolerance of ±1mm. This creates component fragmentation with no functional benefit and makes repairability far more difficult than it needs to be.

This proliferation of near-identical components drives up energy use through redundant manufacturing, duplicated testing, and fragmented logistics. Pullen believes that greater standardisation – as seen in sectors like USB power delivery – can help stabilise procurement and reduce both material waste and supply chain emissions.

Kert’s views align with this, as he believes that shared data standards can achieve the same outcome digitally. By integrating carbon as a common data field in procurement systems, it allows sustainability to become measurable across every link in the chain, uniting design and data in one continuous feedback loop.

Pullen also notes the importance of long-term procurement strategies over short-term cost-cutting. He believes that by securing stable, long-term contracts, companies can plan manufacturing capacity more efficiently, avoid the carbon costs of constant retooling, and cultivate stronger supplier relationships that support sustainability goals.

Industry momentum

Sluicebox is one of several companies providing visibility into the environmental impact of electronics. Founded by engineers and scientists from NASA, Amazon, and Uber, it helps electronics and semiconductor firms automate and scale product-level carbon calculations, delivering ISO-compliant data for over 99% of electronic components globally. The platform has been independently evaluated by TÜV Germany.

While Pullen argues that many firms still focus too heavily on short-term gains, some of the largest electronics manufacturers are beginning to take a longer-term view. Companies such as Apple, Samsung, and Google are demonstrating that sustained investment in renewable energy and design efficiency can yield both environmental and economic resilience. Apple, for instance, reported in 2024 that its suppliers now source nearly 18GW of renewable energy, preventing around 22 million tonnes of CO₂ annually. Samsung and Google have expanded renewable agreements with suppliers in Taiwan and China, while data centres in the UK and Europe are increasingly powered by renewables.

Beyond energy sourcing, product design is a key factor when considering emissions reduction. Using recycled aluminium and lower-carbon materials in enclosures, optimising software for low-power operation, and extending device lifespan all help balance the environmental cost of production.

The bigger picture

Reducing the energy impact of consumer electronics requires a holistic view – from the materials mined to the way devices are designed, assembled, and distributed. Forefront RF’s Foretune Technology, Sluicebox’s Component Carbon Intelligence, and Pullen’s design philosophy of repairability and standardisation show that sustainability improvements can occur not just at the surface level of packaging or energy sourcing, but deep within the circuitry, supply chain, and design mindset itself.

Aside from electricity, energy savings can come from design and materials. Lighter phones require less metal (reducing mining and transport energy), and low-power chips reduce manufacturing energy. Software also matters: more efficient operating systems and components cut emissions. However, the biggest gains come from simply keeping devices longer. Thus, hardware durability, repairability, and long-term support are crucial emissions reducers.

In part 3, I take a look at electronic waste and end of life.

Bib list:

[1] Zhang, Z. et al. Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science & Engineering, University of Washington (2024) ‘DeltaLCA: Comparative Life-Cycle Assessment for Electronics Design’, ACM Digital Library. Available at: Zhihan_DeltaLCA_IMWUT2024.pdf

[2] Istrate, R., Tulus, V., Grass, R.N. et al. ‘The environmental sustainability of digital content consumption’ (2024), Nature Communications 15, 3724 (2024). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-47621-w

[3] Martin Kögler. Et al. ‘Sustainable use of a smartphone and regulatory needs’ (2024), Wiley Online Library. Available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/sd.2995?utm

[4] Lieven Eeckhout, Ghent University, Belgium, ‘Sustainable Computer System Design’ (2025), NUS – National University of Singapore. Available at: https://researchweek.comp.nus.edu.sg/Slides%202025/Lieven%20NUS-CS-talk.pdf?utm