P3: Reducing waste, EoL, and conclusion

In April 2025, a national survey commissioned by UNA Watch found that people would rather replace their technology than repair it. And, to be honest, repairability is not always easy, quick, or cheap. In this regard, I think it is fair to say that consumer electronics are one of the biggest contributors to global sustainability challenges.

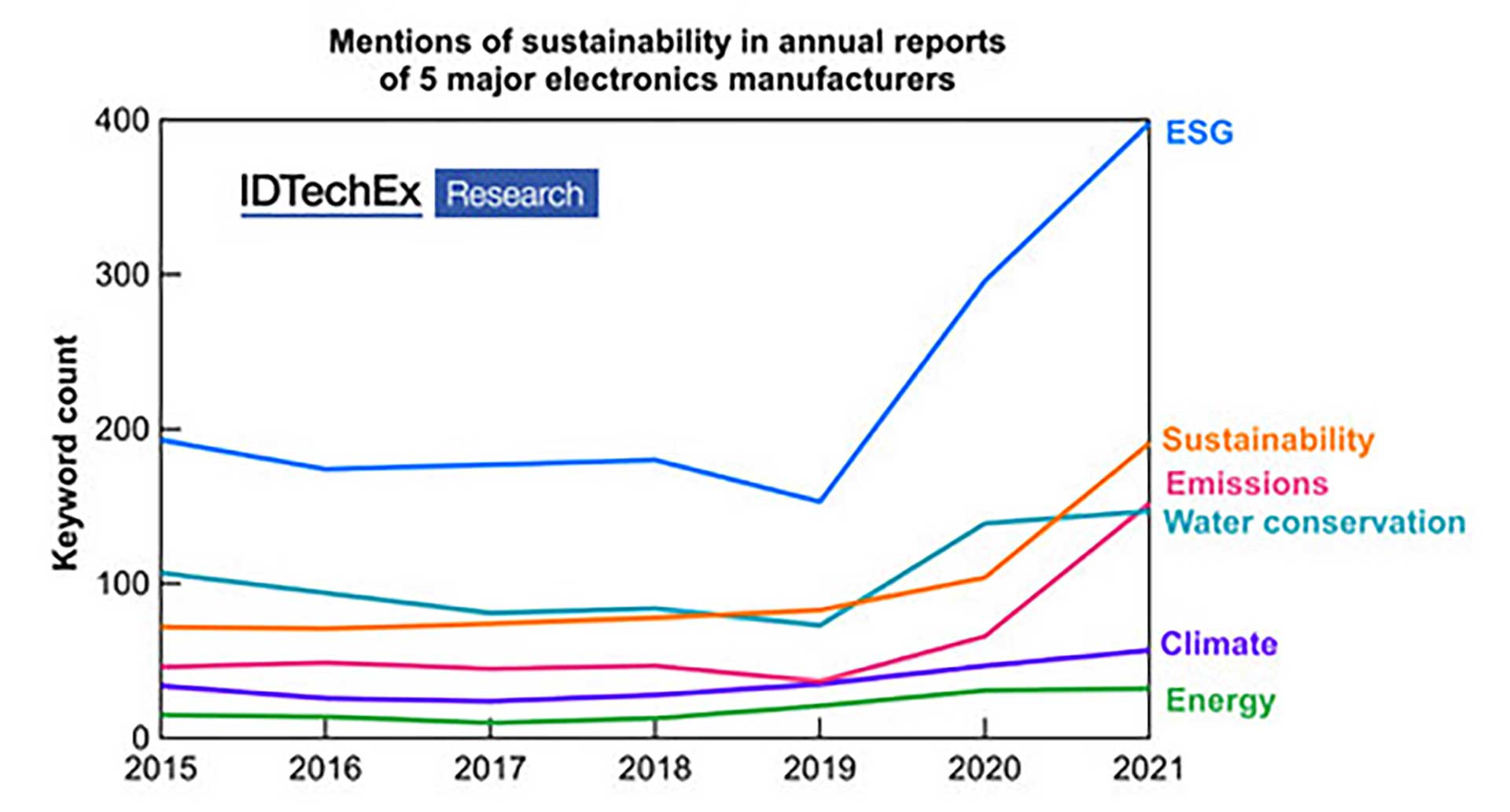

Yet, there may be hope on the horizon. Consumer thinking is reported to be evolving to consider the wider impact of choices, at least from an environmental perspective. According to Greg Petro, a contributor at Forbes, a 2022 ‘First Insight Sustainability Report’ stated that Gen Z has “outsized influence” on their Gen X parents and Boomer grandparents. Furthermore, “consumers across all generations […] are now willing to spend more for sustainable products.” Perhaps this is a glimpse into the future of consumers driving trends rather than clever marketing campaigns, and ipso facto, driving the need for procurement teams to look deeper than simply price and performance when it comes to supply chain considerations. Perhaps the three Ps of procurement should be price, performance, and product serviceability. In fact, over half of consumers say they are willing to pay a premium on eco-friendly products, whilst 70% are open to purchasing sustainable, energy-efficient products if they are reasonably priced.

Not only this, but companies such as In2tec, a sustainable electronics company focused on developing and applying more sustainable manufacturing techniques in electronics, and Component Sense, a specialist in excess and obsolete electronics components that helps manufacturers manage surplus stock, are actively seeking to prevent waste rather than rely on reactive recycling. Plus, individuals like Creative Technologist, Jude Pullen, who has worked on projects that investigate the waste and damage caused by a disposable economy, are fighting for the right to repairability.

Although consumer attitudes and innovative companies help, the lifecycle infrastructure behind the electronics is still a systemic barrier. Because even with cleaner energy and smarter design, some of the biggest challenges for procurement teams and supply chains are obsolescence, driving up costs, pushing grey market inflation, and extending production timelines, as well as a lack of regulation.

In Part 3, I explore the fight to repair and end-of-life strategies to find out if we can turn today’s “take-make-dispose” model into a more circular and sustainable system. I will focus on what happens when devices reach the end of their life: the challenge of electronic waste (e-waste), how it is managed, and what systemic changes are needed to make the industry more sustainable.

For this third and final part of the series, I’d like to once more send a big thanks to:

Jude Pullen, Creative Technologies, for his insights and for his continued enthusiasm for repairability in the electronics industry.

Faki Saadi, Director of Sales, at enterprise mobility and IoT management company SOTI, for sharing his insights on how right-to-repair and lifecycle thinking reshape enterprise mobility and procurement strategies.

Recap and looking ahead

In parts one and two, I looked at the journey of consumer electronics over the past fifty years, as well as raw material extraction and exploring the energy required to power consumer electronic devices, through to the impact of manufacturing, which accounts for roughly 70-80% of lifecycle emissions, and the global logistical delivery chains. As we read in part two, consumer electronics continue to expand, with revenues projected at around $1 trillion in 2025 and growth forecasts ranging between 2.8% and 6.6% CAGR through 2030. I also spoke to companies and individuals who are working to turn sustainability efforts into action, and profitably so.

This brings me to the last link in sustainable procurement in consumer electronics. After devices have been mined, designed, created, and sold, what happens when they reach their end of life? And what does this mean for procurement teams?

EPR and its effect

Extended producer responsibility (EPR) is a linchpin that moves the costs and risks of end-of-life management onto producers, and it is steadily evolving in the UK and EU. This means that under EPR frameworks, manufacturers are legally required to finance separate collection, transport, treatment, and information reporting for products they put on the market, internalising waste management costs that would otherwise be passed on to the government or consumers.

By using this methodology, it encourages more sustainable product design and can influence unit cost and total cost of ownership for procurement teams, because the costs of recycling obligations and takeback schemes are increasingly reflected in product pricing and supplier agreements. This forces manufacturers to think carefully about what they are producing.

In the EU, EPR schemes are being refined to address emerging technology such as smart devices and include mechanisms like the Digital Product Passports, which are designed to enhance the traceability of materials and recyclability of data.

These changes mean that procurement teams must now assess supplier readiness for EPR compliance and understand how those costs and responsibilities will be shared or passed through supplier contracts.

Let’s zoom out now and look at the scale of the e-waste problem.

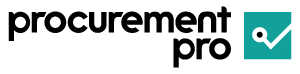

Piling up the waste

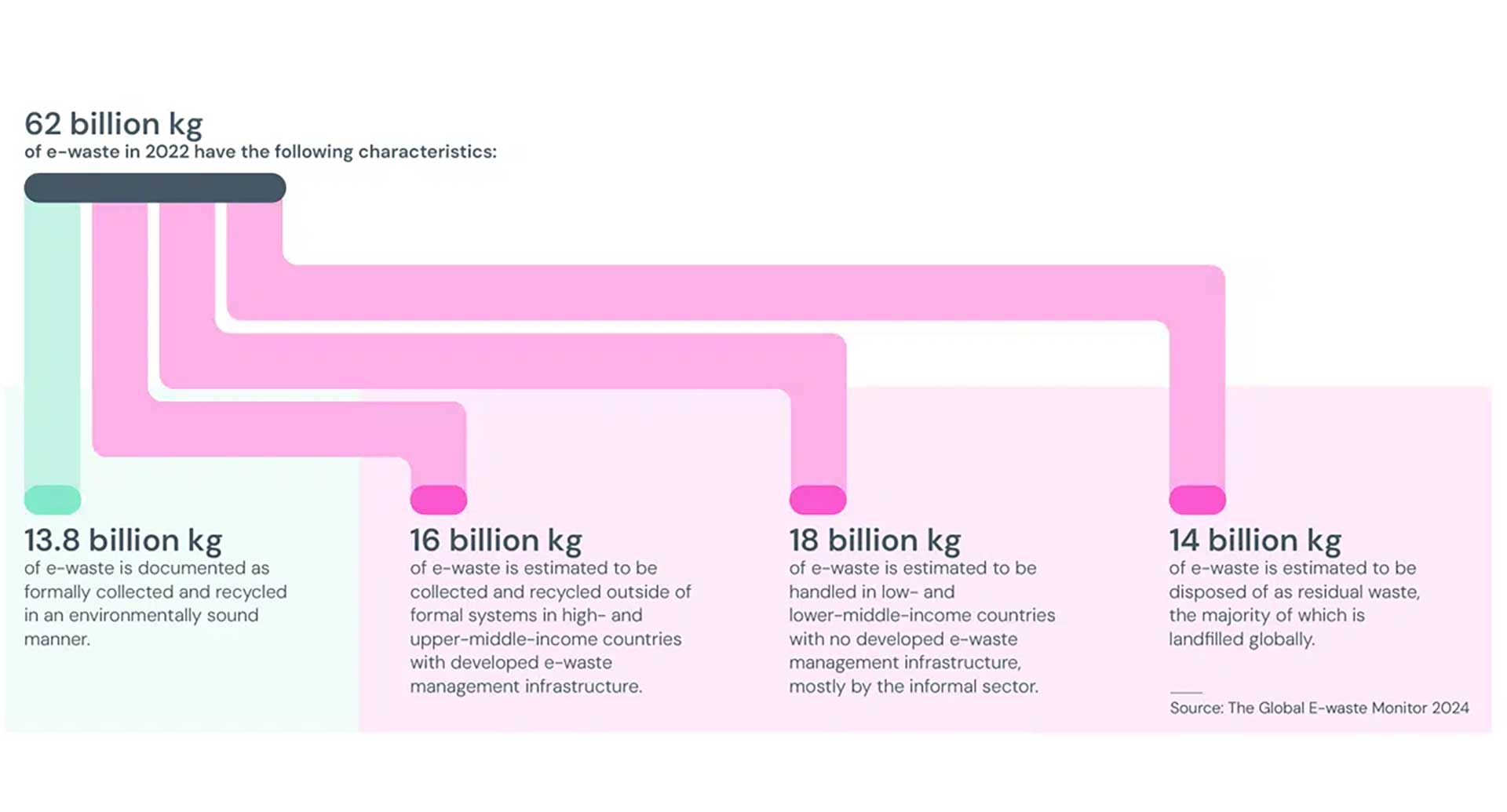

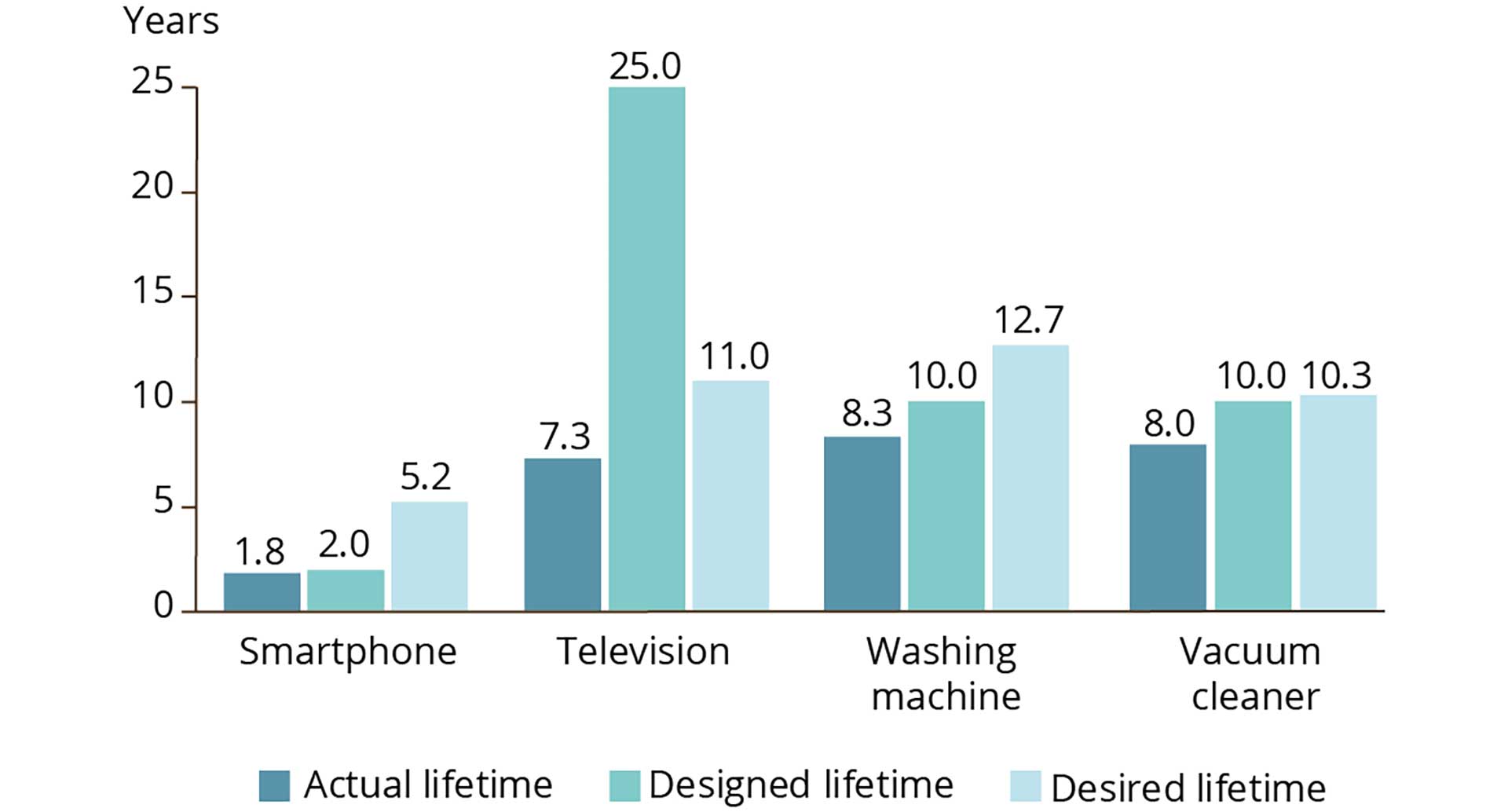

Consumer electronic products are often, unfortunately, designed with shorter lifespans than they were in the past. This can be because of anything from the fragility of components and non-upgradable parts, or planned obsolescence and withdrawal of software support, making longevity difficult, if not impossible.

One of the biggest drivers of consumer electronic waste is the speed of technological advancement. If we take the advanced semiconductor manufacturing for consumer electronics as an example, semiconductors are obsoleted by product cycles or supplier discontinuation within around two to five years, meaning chips, which are reliable for possibly decades, are retired well before their physical end of life because devices are replaced or the part is discontinued. As we read back in article one, every year new smartphones are coming to market, so before the most energy-intensive component is obsolete, the device is already outdated as newer models are sold. This is a significant burden on procurement sustainability.

Yet, if devices were designed with repair and maintenance in mind, the results would offer financial and operational advantages for businesses. As Faki Saadi, Director of Sales UKI at SOTI, notes: “By maintaining devices, organisations can avoid costly replacements and reduce time spent implementing new equipment or arranging waste removal. Repairs also minimise downtime, as they are often faster than procurement and setup of new devices.”

The fast pace of AI and processor advancements is another dilemma – how can devices remain relevant without generating mountains of waste? The solution potentially lies in modularity.

Pullen explains: “The only responsible way forward is to make AI-driven devices upgradeable. Having grown up as a kid who has built a Pentium 486 from components, upgrading as necessary, I’m not ‘harking back to the good old days’, but I can’t help but wonder if the ‘pendulum’ has not swung too far the other way – with little or no capability to ‘swap-out’ a processor, graphics card, etc.”

Pullen continues: “The only responsible way forward is to make AI-driven devices upgradeable. If a company permanently soldered a processor to the board, the entire device would become obsolete within a few years. A modular approach, where critical components can be swapped out, extends a product’s lifespan without sacrificing performance.”

This is already being explored in industries like smartphones, for instance, by Fairphone, but a broader adoption could fundamentally change how electronics are produced and consumed.

By integrating these strategies across the entire lifecycle of consumer electronics, from raw material extraction to end-of-life management, the industry has a real opportunity to build a more sustainable future.

“Businesses must ask themselves: how beneficial is this new technology, and does it offset the negative impact on the environment?” said Saadi. By making long-term value a priority over short-term convenience, companies can play a starring role in reducing e-waste and creating a sustainable industry, and all while maintaining profitability.

So, how do we keep these devices in use for longer? Let’s take a look at consumer electronics in use, what are the barriers to repairability, and what can be done about them?

Research by SOTI, found that 69% of businesses discard mobile phones unnecessarily.

Saadi explains: “With the quick pace of technological developments and the latest mobile devices rolling out every couple of months, it’s easy to get swept up in wanting (or thinking the company needs) the latest devices. Businesses assume newer devices will integrate more seamlessly with emerging technologies, but in many cases, there’s no real need to upgrade.”

Beyond perceived obsolescence, there is also often a lack of awareness around repair options. Misconceptions that repairs are costly and time-consuming lead companies to opt for replacement out of convenience, which increases electronic waste and puts pressure on supplies.

Saadi highlights that “the most prevalent group likely to replace laptops and tablets globally – whether they are working or not – are those in the technology sector (47%).” Saadi advises on some practical steps businesses can take to extend device lifespans rather than replace them:

- Using battery dashboards to monitor charge cycles and temperature

- Turning on the device’s battery saver mode

- Using data to predict when batteries will fail and proactively replace them

- Shortening the idle time before the device goes to sleep and/or locks

Balancing innovation and sustainability

Some of the biggest barriers to device longevity are manufacturers using proprietary parts, complex software, specialised tools, glued-in components, bonded-in batteries, and proprietary fastenings. Not only does this make repair difficult, if not impossible, but the design decisions made at the production stage also directly affect waste outcomes and hinder circular business models for reuse, repair, and refurbishment.

For procurement teams, specifying design features that allow for serviceability, in addition to performance specifications, when evaluating suppliers and products, will become increasingly important as ESPR legislation rolls out.

Governance and standardisation

Procurement strategies should also account for evolving legal rights and obligations that affect product life extension. In the EU, the Right to Repair Directive complements eco-design requirements by giving consumers and buyers the legal right to have products repaired at a reasonable price and by requiring manufacturers to provide spare parts and repair information for affected products. This directive is expected to roll out nationally by mid-2026, and, when paired with broader product sustainability regulations, it is intended to ensure that products are designed not only for initial performance but also for longevity and repairability.

Right-to-repair legislation is giving businesses greater flexibility in how they maintain their devices. Saadi explains: “Enterprises are no longer locked into one supplier, allowing them to adopt more sustainable mobility strategies. This means easier maintenance and repair of mobile devices, reducing downtime, and improving productivity.”

While regulatory frameworks are still evolving, companies that embrace repairability early will be better positioned for future compliance.

If we step away from enterprise, the Right to Repair movement is gaining momentum as consumers and policymakers push for greater product longevity. Products such as modular smartphones show that designing devices for easy component replacement extends lifespans and reduces disposal costs.

Pullen points out that, historically, mobile devices had replaceable batteries and parts, making maintenance easier and more straightforward. Yet, modern designs prioritise aesthetics, such as thinness, over repairability, which often increases EoL costs.

Pullen further explained that whilst some design features are cited as barriers to repair, many are overstated. Procurement teams evaluating long-term device costs should look at whether the claimed limitations actually affect maintainability or longevity.

However, the regulation landscape is evolving, and procurement teams must prepare. Let’s look now at sustainability regulation.

What does regulation look like?

The Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR) came out in 2024. But what is it, and what does it mean for the future of electronic sustainability?

What is ESPR?

The ESPR is an EU framework designed to make products more sustainable, easier to repair, durable, and easier to recycle. The framework sets out rules for how products should be designed, made, and documented throughout their lifetime. Although it builds on the older Ecodesign Directive, ESPR is broader because it applies to almost any physical good, including electronics.

For electronics, ESPR is, essentially, asking manufacturers to think ahead. A product should be designed so that materials are easier to remove, components are easier to repair or replace, and recycling companies can extract value without unnecessary complexity. It also brings in requirements for clearer information on durability, repairability, energy use, and the materials contained in each device.

What ESPR means for end-of-life electronics

ESPR aims to reduce the amount of electronic waste that ends up in landfills or incineration. If a laptop, smartphone, or router, for example, is designed with disassembly and material recovery in mind, the recycling process becomes more efficient. ESPR also pushes for fewer mixed-material parts, fewer glues that prevent separation, and greater access to repair information. The combined effect is a smoother path from discarded product to recovered materials, rather than a pile of waste that is difficult to process.

The framework also creates more pressure for transparent waste handling. Organisations will need to show how products are managed when they reach the end of life, and recyclers will be able to access better information about what is inside each device.

But how does ESPR work in reality? This is where digital product passports come into play.

What is a Digital Product Passport?

A digital product passport (DPP) is a digital record attached to a physical product, something akin to a data sheet that follows a device through its life, from manufacturing to end-of-life recovery. It holds product information such as the materials used, expected lifetime, repair options, spare parts availability, energy profile, and recommended recycling steps.

A DPP is accessed through a data carrier, usually a QR code or an NFC tag, that links to a secure database. The information sits in a standardised format so that anyone in the value chain can read it, but access to detailed data can be limited to authorised parties.

How DPPs work

The passport is created during manufacturing. As materials move through the supply chain, each organisation adds the information it is responsible for. When the product enters the market, the code on the device gives retailers, users, repairers, and recyclers access to the level of information they are allowed to see.

When a device reaches its end of life, recyclers can scan the product and immediately see which materials can be recovered, which components require careful handling, and the most efficient sequence for dismantling.

How DPPs support the ESPR mandate

DPPs are the enforcers of the broader aims of ESPR to make it workable. ESPR sets the requirements for durability, repairability, recycled content, and design for disassembly. The DPP shows whether these requirements have been met and provides the practical information needed to implement them.

For electronics at their end of life, DPPs mean that recyclers will no longer have to guess what is inside a sealed unit. Instead of manually testing or shredding devices to discover their contents, they can follow accurate data. This reduces waste, increases the recovery of valuable materials, and improves safety by identifying batteries, magnets, PCBs, or hazardous substances.

What all this means is that the ESPR sets the rules for more sustainable electronics, and DPPs provide the data trail that allows those rules to be followed in practice.

By designing products with disassembly and repair in mind, engineers create devices that are easier and safer to recycle. For procurement teams, this mindset translates into long-term cost optimisation and simpler supplier management. With the roll-out of ESPR and Digital Product Passports, these practices will move from best practice to regulatory requirement, giving teams that already prioritise serviceability an advantage in compliance, supplier choice, and negotiation.

Reverse engineering for sustainability

The challenge of electronic waste is often framed as a problem of consumption, but according to Pullen, it’s also about a shift in mindset: “Reverse engineering … is precisely the mindset we need for repairability. E-waste recycling plants want to know how to get a battery out as quickly as possible without damage, both to reclaim valuable materials and to prevent fire risks. A product designed for easy disassembly, more often than not, is a product designed for sustainability.”

Engineers designing with the end in mind means that procurement teams will benefit from long-term cost optimisation, enhanced supply chain resilience, and simpler supplier management. For procurement teams that already consider product serviceability alongside price and performance, the roll-out of ESPR and DDPs means that their existing practices will become validated and formalised, putting them ahead of the curve. It also means there is greater scope for negotiation and manufacturer/supplier choice.

The business case for repairability

For companies hesitant to shift towards repairable designs, there is a pragmatic argument: sustainability can be profitable.

“Companies worry that sustainability threatens profits, but the reality is different. You can maintain margins by evolving your maintenance and spares game. Ignoring this shift will be damaging – compliance regulations will tighten, and those that fail to adapt will fall behind. The financial projections of companies unwilling to change will end up collapsing,” explains Pullen. “Only an elite few will be able to ‘pass the cost on to the consumer’ and keep current practices, the rest will be the other extreme of cheap, disposable ‘fast fashion’ from companies trying to evade legislation by selling fast, closing down, starting up under a different legal entity – one only has to look at Vapes for this reckless business model in some vendors.”

The shift towards modular, repairable products could create new revenue streams through extended warranties, spare parts, and upgradeable components, rather than relying on complete product replacements.

The economics of standardisation

One of the biggest barriers to repairability is the sheer variety of proprietary components. Standardising key elements, such as batteries, could transform sustainability efforts and enable procurement teams greater autonomy of choice.

“Some companies insist on ‘exotic’ battery designs – slightly altered in size just enough to make third-party replacements impossible. But in reality, the difference is often negligible, a rounding error. If the industry committed to standardising even 100 battery sizes, it would significantly reduce waste, lower costs, and make repairs far easier for consumers,” said Pullen. “Those who insisted on having ‘bespoke’ batteries would ideally pay a tax for creating a harder-to-replace item. As with the debacle on phone chargers, it seems we need more universal ‘USBC-thinking’, rather than everyone making a ‘special thing’ which is damaging to the environment.”

Legislation may be needed to enforce such changes, but there is clear logic in creating an ecosystem where repair is not only possible, but practical and cost-effective.

A cultural shift in how we “consume”

It’s not only the components that need a rethink, but also the language around ownership. The term “consumer” implies disposability – an endless cycle of use and discard. Instead, we need to view electronic devices as long-term investments.

Pullen said: “Perhaps we should stop calling this the ‘consumer electronics industry’ and instead think of it as the ‘buyer industry.’ The word ‘consume’ means ‘to use up, expend’ – but a shift in terminology could reflect a shift in mindset. The future must be about stewardship, not single-use, throw-away over-consumption.”

End-of-life disposal

Even with reuse and repair, every device eventually reaches end-of-life. At that point, sustainable disposal is crucial. Modern e-waste recyclers use mechanical shredders and chemical processing to extract metals from circuit boards and batteries. However, not all recycling is equal. Formal recyclers (often R2- or e-Stewards-certified) follow strict environmental, health, and data-security rules. For example, a firm certified under the R2 Standard would dismantle phones, sort plastics and metals, and smelt components to reclaim copper, gold, silver, and lithium. Certified facilities ensure, for example, that lithium-ion batteries are removed safely (preventing fires) and data is destroyed. By contrast, “informal” recycling (common in some developing countries) can expose workers to toxic dust (from acid baths) and often recovers less. This brings the point about raw material extraction from part one full circle – without proper policies in place, there are ethical concerns around electronic devices that aren’t set up for quick, easy dismantling and disposability.

Sustainable procurement policies insist on proper certification. For instance, the ANSI-accredited R2 Standard is described as the world’s most widely adopted electronics reuse/recycling standard. It covers everything from data wiping to environmental controls during shredding. In the UK/EU, many electronics recyclers hold R2 or equivalent certification, and buyers and disposers should require certification for the processors they use.

When equipment reaches EoL, insecure handling or inadequate destruction of data can expose organisations to material risk, such as regulatory fines, not to mention damaging their reputation.

Despite regulation under the Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE) Directive, collection and recycling are uneven across markets. Recent evaluations show that nearly half of WEEE generated in the EU is not formally collected, and only around 40% is recycled. This is, in part, due to the fragmented implementation of producer responsibility schemes and inconsistent treatment standards, which highlight the ongoing operational challenges in downstream waste management. When it comes to WEEE, procurement teams should not assume uniform service levels from recycling partners. Understanding local collection performance, certification of recyclers, and the specifics of national WEEE schemes can help minimise compliance risk, improve reporting accuracy, and ensure responsible disposal pathways for end-of-life assets.

UK regulatory frameworks, such as the trans-frontier shipment rules, distinguish between used electrical equipment and waste, meaning only tested items ready for direct reuse can lawfully be exported without notification; otherwise, they must be treated as waste. Misclassification of this can lead to illegal shipments and compliance breaches, which reinforces the need for clear chain-of-custody protocols with recyclers and asset recovery partners. Stringent IT asset disposition (ITAD) services that provide verified data sanitisation and documented destruction can reduce this risk.

Effective end-of-life management is not only about compliance, it also captures residual value from assets. Secondary markets for refurbished or remanufactured electronics can provide cost benefits and support circular economy goals, but they also require standards for safety and transparency.

This is where emerging frameworks, such as the EU’s DPPs I mentioned earlier, will provide machine-readable information on product composition, repairability, and material origin, which will help procurement teams in decision-making for reuse and remanufacture pathways. Partnering with credible refurbishment and remanufacturing channels that use this traceability will help strengthen risk management and support sustainability agendas.

Clear contractual terms on take-back, buyback, or exchange programmes, aligned with EPR requirements, can also help recapture value and reduce waste disposal costs.

Conclusion

Across this three-part series, one message has remained consistent: electronic sustainability is not a single problem with a single solution, but the cumulative outcome of decisions made across the entire product lifecycle.

The evolution of consumer electronics over the past five decades has transformed from niche innovations into indispensable tools that shape modern life. Yet this rapid expansion has come at a high environmental cost.

The industry’s dependence on finite raw materials, energy-intensive manufacturing processes, and short product lifecycles has created a system that is both resource-hungry and environmentally unsustainable. The resulting pressures – from escalating e-waste to rising greenhouse gas emissions – reveal a sector at a critical inflection point.

The path to long-term sustainability – and the continued success of consumer electronics – will depend on a fundamental shift in how products are designed, manufactured, and managed throughout their lifecycle.

What we have learnt is that manufacturing dominates lifecycle emissions, that valuable and finite materials are routinely lost at the end of life, and that frequent replacement cycles accelerate both environmental damage and cost. We have also seen that repairability, standardisation, and design for disassembly can dramatically reduce emissions, extend device lifespans, and improve recycling outcomes. Importantly, sustainability and commercial resilience are not in opposition. Longer-lasting devices, simpler supply chains, and fewer emergency replacements support cost control, operational stability, and risk reduction for procurement teams.

What is changing is the wider ecosystem around electronics. Regulation is evolving from guidance to obligation. Frameworks such as Extended Producer Responsibility, right-to-repair legislation, the Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation, and Digital Product Passports are beginning to formalise practices that were previously optional. At the same time, data transparency is improving, enabling organisations to understand the environmental impact of sourcing, design, and end-of-life decisions with greater accuracy. Consumer attitudes are also shifting, applying pressure on businesses to demonstrate responsible stewardship rather than rapid turnover of devices.

What must happen next is a coordinated shift in priorities. Electronics must be designed with longevity, repair, and end-of-life recovery as core requirements, not afterthoughts. Procurement teams must look beyond upfront price and performance, embedding serviceability, lifecycle data, and supplier accountability into purchasing decisions. Manufacturers and suppliers must adapt business models to support maintenance, upgrades, and reuse, rather than relying on replacement-driven growth. And regulators must ensure that new frameworks are implemented consistently, giving the market clarity and confidence.

Ultimately, the future of consumer electronics will be defined not only by innovation in functionality but by innovation in responsibility. Ensuring the longevity of both the industry and the planet requires a collective commitment to circularity, transparency, and smarter design.

If the industry succeeds, electronic devices will remain in use for longer, waste will be reduced at source, and valuable materials will circulate rather than disappear into landfill. Sustainability, in this context, is not about consuming less technology, but about using it better, for longer, and with greater responsibility. The choices made today will determine whether the next era of consumer technology is one of sustainable progress or continued ecological strain.