In a world where “everything’s got electronics in it these days,” as Paul Green, Sales Director for Northern Europe, Middle East & Africa at Rochester Electronics put it, the risk of component obsolescence has become a concern, not just a supply chain nuisance.

A recent webinar, sponsored by Flip Electronics and hosted by Paige Hookway, Managing Editor at Procurement Pro, brought together four industry specialists to explore how rapid technology cycles, AI, and geopolitical shifts are reshaping obsolescence management – and what organisations can do about it.

The growing pace – and scope – of obsolescence

From the outset, all four panellists agreed: obsolescence is not only accelerating, it’s touching more sectors than ever.

Green described a sharp expansion beyond traditional sectors: “Traditionally, we were supporting aerospace and defence primarily, but more and more, it’s so many others than that. Everything’s got electronics in it these days.”

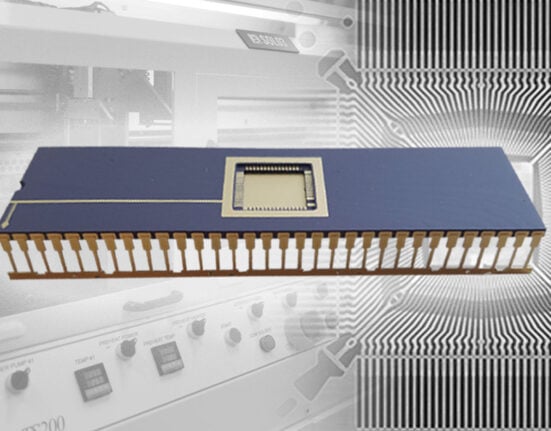

He noted that around half a million parts went end-of-life last year, forcing companies to decide whether they can migrate to a next-generation component – or face much tougher choices when no obvious successor exists.

Matthew Amato, Head of Global Marketing and Growth at IBS Electronics Group pointed to two converging trends: faster EOL (end-of-life) and poor visibility.

“The speed at which the semiconductor electronic components are reaching end of life is accelerating, but also supply chains sometimes lack visibility … part change notifications are reactive rather than proactive.”

This mismatch between product lifecycles and equipment longevity is especially acute in sectors where systems are expected to operate for decades, not years.

Obsolescence as a discipline – not a side task

A central theme was that obsolescence management cannot simply be a side responsibility of already stretched engineers or buyers.

Oliver Hoffmann, General Manager EMEA at Z2Data argued that: “Obsolescence management is like an optimistic collaborative discipline which needs to be done by a certain amount of people or of a team … I’m normally finding undersized teams of obsolescence management.”

In many smaller companies there is no ‘obsolescence manager’ at all; in larger ones, responsibilities are often scattered across procurement and engineering, with no coordinated strategy. The result, he said, is that organisations miss out on preventive, data‑driven approaches that could dramatically reduce firefighting.

Hoffmann illustrated the shift in engineering workload over recent years: “Before the pandemic … engineering managers told me, yeah, it’s about 50/50 [between new development and maintenance]. Since the pandemic … 20% of our time is on innovation, and 80% is firefighting … We are at like 40 to 60 meanwhile… but we are not yet back on pre pandemic.”

Data, forecasting and AI: from firefighting to prevention

Modern obsolescence management is increasingly powered by predictive data and AI‑driven tools.

Amato described how IBS Electronics uses AI tools to monitor lifecycle and availability in real time: “We have AI enhanced tools that help us to identify shrinking availability through the authorised channel … changes in price increases, other end of life notifications, allocations that are tightening, lead times increasing.”

The message was clear: integrating such data into EDA, PLM, or ERP systems allows organisations to embed obsolescence risk checks directly into the design process, rather than discovering problems only when PCNs or shortages hit.

Redesign vs. alternatives vs. remanufacturing

Deciding when to redesign a board, qualify a second source, or seek long‑term manufacturing support is rarely straightforward.

Green stressed that the right answer is highly application‑specific: “If you are a customer making a commercial type of product, it’s going to be a lot easier … than it might be for someone involved in aerospace or a medical customer … It’s not one shape fits all.”

Bill Bradford, President, Flip Electronics, emphasised that economics and certification burdens often dominate the decision: “In some cases, it may not just be the redesign, but it might be a months or years long qualification recertification, in the case of medical equipment … At what point does it make more economic sense to bite the bullet [and] launch an expensive and time‑consuming redesign, versus really trying to find alternative parts?”

Both Flip and Rochester support another path: licensed remanufacturing of EOL components, extending life under original specifications and test programmes.

“We continue to manufacture, build out products under a licence agreement with the original manufacturer to continue to extend the life of critical components,” said Bradford.

“We have active and obsolete parts available in stock, and … ongoing manufacturing … so we can support [customers] for potentially decades to come,” notes Green.

Second sources, hybrid distribution, and the grey market risk

When no direct replacement exists, or when a legacy component has no smooth migration path, the panellists warned strongly against unmanaged grey market sourcing.

Amato argued for “creativity and collaboration” with trusted partners: “Sometimes we do need to go to the open market, but when we go to the open market, how do we do so safely? How do we ensure that certified vendors are audited?”

He stressed starting with recognised certifications such as ISO, AS9120 and AS6081 as a baseline for evaluating second‑source and hybrid distributors: “I think certifications is a great place to start … these certifications are directly related to help to mitigate these challenges, for example, obsolescence mitigation, counterfeit mitigation.”

Bradford added that the risk of counterfeit is significantly higher once devices go EOL: “We perform studies that show that counterfeits are much more prevalent in semiconductors that have been end of life than they are in active components … customers start to pursue product in the grey market. That’s where there’s inherent risk.”

Key takeaways: proactivity, partnership, and constant vigilance

In closing, each panellist offered a single key message.

“Proactive mitigation is obviously at the forefront, but it’s not always possible. So find a partner that can … pivot and support you … and think more proactively from the early design stages,” said Amato.

“Be proactive, think critically, observe, and try to anticipate the outcome of events, even if that kind of events haven’t been there yet,” notes Hoffmann.

“Constant vigilance, both on the reactive side and … aligning with creative partners … more often than not, we can find a way to make it happen,” said Bradford.

“Things happen … fires in factories and so on. You can’t avoid [them] but just try and plan for as much as you can by working with others and collaboration within the company itself … not just today, but the future of the plan ahead,” notes Green.

The overarching message of the webinar was clear: you cannot stop obsolescence, but with the right data, partners, and internal collaboration, you can turn it from a crisis into a manageable, strategic process.