For much of the 1990s and early 2000s, the military and aerospace (mil/aero) sector was a subdued corner of the European semiconductor industry. Growth hovered around 2-3%, design cycles stretched seven to 10 years, and only a handful of companies focused on the space. There was a common perception that mil/aero was technically interesting but commercially unrewarding – no one was going to get rich waiting a decade or more for a programme to reach volume.

How times change. The market for defence equipment is now one of the fastest growing, driven by a rapid and profound political shift. After decades of relative calm, the resurgence of conflict and increasing pressure on NATO members to shoulder a greater share of defence costs have fundamentally changed spending priorities. Defence budgets across Europe are accelerating from 1.5% to 2% of GDP toward targets as high as 5%, more than doubling spend. That’s not a short-term spike. Most indicators point to a steady and significant increase through at least 2035.

State of the art vs. state of the ark

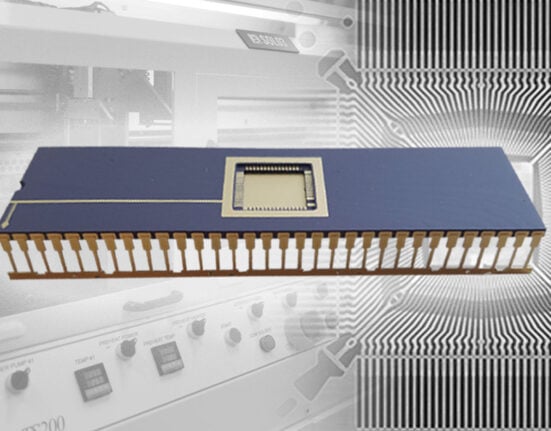

For procurement teams, the challenge lies in managing two very different timelines. Modern warfare dictates modern armament, so on one side is the pace of technological innovation. Drones are the clearest example. In little more than a decade, they have evolved from consumer gadgets into sophisticated, long-range military weapons with an array of payloads and capabilities. Accelerating demand has drawn both traditional defence primes and new entrants into the sector. But as technology lifecycles compress and scarcity comes into play, finding enough components for designs featuring already-passé components will require a level of obsolescence jujitsu the mil/aero sector hasn’t seen in a while. It’s not unusual to find that a majority of components on the bill of materials are obsolete before the programme heads to production, leapfrogged by iterative updates or entirely new form factors.

On the other side are exceedingly long defence equipment development cycles. Complex, sophisticated military equipment can take years to design, test, and validate, making redesign costly, time-consuming, and impractical. Furthermore, a significant cohort of military equipment is engineered for decades of service. Durable platforms such as aircraft, ships, and armoured vehicles are expected to last 30, 40, or even 60 years in the field. Procurement teams are accustomed to managing inventory for repair and replacement. They’re not as adept at doing so for militaries breathing new life into legacy programmes replete with prior-generation hardware. I’ve seen instances where the majority of components in a bill of materials are already declared obsolete before the first piece of equipment rolls off the production line.

Obsolescence: the quiet constant

Despite its inevitability, obsolescence has long been a slightly uncomfortable topic for many. I would humbly suggest it’s time to get over it. As dormant platforms return to mainstream production, demand for prior-generation semiconductors, electromechanical devices, and spare parts will only increase – and so will the competition for them. A resolute path is required.

The most important shift for procurement teams is recognising where obsolescence decisions are now being made. They are no longer reactive choices to be dealt with after a part reaches end-of-life (EOL). Increasingly, obsolescence planning starts with design. Engineers, working with their component manufacturing and supply chain counterparts, are expected to address lifetime support from design through production and into post-production maintenance, repair and disposition. ‘Concept to completion’ has moved from marketing slogan to mission necessity.

The EMEA supply chain

Europe’s long-established military ecosystem remains concentrated in the UK, France, Germany, and Spain, which together account for roughly 80% of the region’s total mil/aero addressable market. These primes and their contractor networks are global in nature, but the supply chain is under pressure. The political shift in Europe happened fast, leaving little time to rebuild inventory or supply chains from scratch.

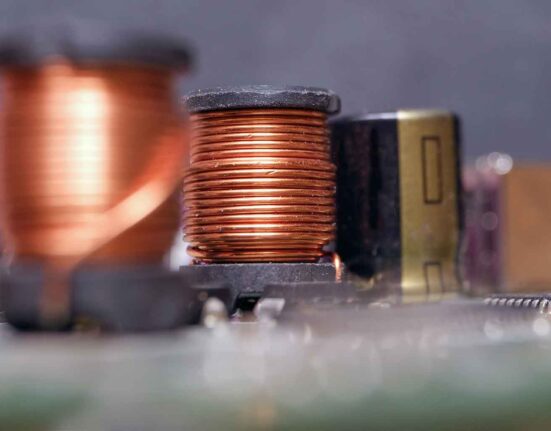

Once last-time buys are completed, mainstream distributors typically exit the picture. Responsibility shifts to manufacturer-authorised specialists with the financial strength to hold inventory, or secure wafers and dies for remanufacturing, for 10 to 15 years or more. This is not trivial work. Managing high-value, slow-moving parts over decades requires a deep understanding of specific mil/aero programmes and close alignment with customers and component manufacturers. It is a shared burden requiring mutual investment, and only a small number of companies have the capabilities and relationships to do it effectively.

What procurement teams should do now

Looking ahead to 2026 and beyond, the mil/aero market will remain buoyant. Elite, high-performance semiconductors will be in demand, but so will those from earlier generations, which are responsible for performance and functionality in legacy equipment, because programmes that were shelved years ago are being revived. The European market for semiconductors in the aerospace and defence industry is forecast to rise from $4.6 billion in 2025 to $6.1 billion by 2030.

Over the next three to five years, the pressure to support these reactivated designs alongside new technologies will increase. Procurement, materials management, and supply chain teams need to work more closely than ever with engineers to protect the viability of equipment in the field and ramping (or re-ramping, as the case may be) to production. Understanding the component lifecycle is essential, too, particularly for microprocessors, RF and microwave components, memory devices, and other crucial parts in high demand. Deep knowledge of mil/aero programmes, from avionics and flight control systems to tactical ground assault weapons and seaborne hardware deployments, is at a premium.

So are established relationships. The time to forge a bond and create an early warning system isn’t in the heat of battle, as it were. An obsolescence strategy is best served in partnership with authorised electronic component distributors that can facilitate lifetime buys and extended-life semiconductor manufacturing to ensure reliable access to inventory no longer in production. In a sector where budgets are rising and obsolescence is accelerating, proactive procurement teams with a long-term perspective will be best positioned to support their missions.

About the author:

Nigel Watts, Founder and CEO of Trailing Edge Technologies, entered the electronics industry in 1978 as an engineer. He began his career in sales and marketing in 1981, first at Intel and then at Memec, a global distributor, where he held positions in sales and marketing before becoming managing director. In 1994, he founded a pan-European representative company, Spectrum, which evolved into Ismosys in 2008 and expanded to India and the US in 2017 and 2018. In 2021, Ismosys was sold to Astute. Watts then became EMEA president of WPG, the largest distributor of electronic components in Taiwan. In 2024, he joined Astute as Director of Global Business Development before founding Trailing Edge Technologies in November 2024 to represent Flip Electronics throughout the EMEA region.